For the first time today I participated in Ashes to Go. I joined other people from St. David’s in Austin at the corner of 6th and Congress in front of the Starbucks for 90 minute shift.

I would guess that in the time we were there we imposed ashes on about 60 people. Maybe more. Several things struck me during my time there.

First, people came with openness. Many were appreciative, saying they were not able to get to church and felt the need to have the ashes in any way they could. About half said before receiving ashes that they were Roman Catholic. I was not always sure what they meant by this. All of us imposing ashes simply affirmed their identity and offered them ashes. The attitude of all who received ashes was profound gratitude.

Two encounters stand out for me. One was when several of us imposed ashes on about half of a Segway tour group. The other was when we gave ashes to a Christian from Iran. I don’t think her church in Iran had a custom of imposing ashes but she explained she had just moved to America and wanted the ashes as a sign she believed in Jesus. We gave her a card that we gave to every person that included a list of services for St. David’s. She seemed profoundly moved and said she would come to visit.

Some of my clergy colleagues and I had a Facebook discussion today about where the Easter equivalent to Ashes to Go is. If on Ash Wednesday we offer a public witness in preparation for Lent, when does that happen for Easter? Of course, a public action on Easter Sunday might not be as effective downtown or at commuter stations. But what if something was done on Easter Monday? What if we offered a blessing of the baptismal waters from the Easter Vigil? What if we offered a blessing in the name of the Risen Christ? What if we offered to all those people who pass by us a Blessing on the Way?

Category Archives: Episcopal Church and Anglicanism

Ashes to Go, Blessings on the Way

Filed under Episcopal Church and Anglicanism, Mission, Uncategorized

Good Seed in Rocky Soil

Commemoration of Alexander Crummell

Church Divinity School of the Pacific

Sirach 39:6-11

Ps. 19:7-11

James 1:2-5

Mark 4:1-10, 13-20

“Listen! A sower went out to sow. And as he sowed, some seed fell . . .” (Mark 4.3-4)

Today we commemorate the life and ministry of Alexander Crummell.

Crummell is remembered in as a pioneering African American priest who steadfastly pursued his priestly calling in trying circumstances, who served as a missionary in Liberia, and who was an early voice for African American self-reliance and an influence on later thinkers like Marcus Garvey and W. E. B. DuBois.

In preparing this homily, I initially thought that Crummell was an example of the seed falling in good soil, yielding a great abundance of fruit.

In a way I think that is still true.

The seed of the gospel found good soil in Alexander Crummell and the harvest he brought in was great.

But the seed of the gospel that Crummell himself sowed fell in the hard, rocky soil of pre-Civil War America and the reality of slavery.

And he sowed in the thorn-choked patches of post-Civil War America where the promise of freedom for African Americans gave way to Jim Crow laws and deep-seated institutional racism.

These were the fields Crummell labored in.

His life is worthy of commemoration because he tended the seeds of the gospel in places

where the evil one threatened his harvest and yet he brought in much fruit.

Listen to his story and you will see what I mean.

Crummell sought ordination and was initially admitted to General Theological Seminary in New York, but with the school fearing the loss of financial support, he was told he could only attend if he did not live at the school, did not eat in the refectory or sit in the classrooms.

That is, he could be a student only if he didn’t act like a student.

Crummell turned them down.

He read for holy orders and was ordained in 1844 as a priest in Boston.

Crummell however could not find a permanent position ministering to African American congregations inthe Northeast and rarely received diocesan support that would enable him to fully live out his vocation.

Eventually Crummell went to the African country of Liberia as a missionary of the Episcopal Church, serving there for 20 years.

He imagined Christianity as a great civilizing force that would transform Africa and lead it to higher levels of morality and spirituality.

He envisioned a church headed by Africans for Africans that merged Euro-American technology and learning with African culture.

As well, Crummell hoped that African Americans would emigrate to Liberia to both

escape the racist structures of America and contribute to the transformation of their new home.

Eventually Crummell was forced to abandon his work in Liberia.

He could not secure enough funding from the Episcopal Church and the waves of African American immigrants never materialized.

Returning to the United States, he served as rector of St. Luke’s in Washington D.C.

where he found his new mission in fighting for the rights of African Americans in the Episcopal Church.

Southern bishops, in a resolution known as the Sewanee Canon,sought to segregate African Americans from their local dioceses and place theminto separate missionary dioceses meant for African Americans alone.

Crummell helped establish the Conference of Church Workers among Colored People

in 1883, the forerunner for today’s Union of Black Episcopalians.

Through his leadership this group successfully beat back the racist Sewanee Canon at General Convention and saved the Episcopal Church from further shame.

Given these highlights from the life of Alexander Crummell, the parable of the sower is an appropriate text to use to think about his life.

Crummell sowed the seed of the gospel to inspire Africans and African Americans to lives of greater discipleship, leadership, and creativity.

All the while he sowed his seed in the rocky ground and harsh environment of racism and neglect not just in American society but in the very power structures of the Episcopal Church.

All Crummell ever wanted was to be a priest and for his congregations to have a full share in the life of the wider church.

To do this he had to persevere against what W. E. B. Du Bois, in his essay on Crummell in The Souls of Black Folk, describes as the temptations of hatred, despair, doubt, and fear of failure.

Crummell’s life forces us to both thank God for the grace of perseverance given to the saints but also to ask what we will do when obstacles arise as we sow our seeds of the gospel.

Crummell, writing in the language of his time, tells us that steadfastness and a firm sense of vocation are necessary when confronting hardships.

He says in a sermon titled “Keep Your Hand on the Plough,” that “A man’s thought and interest are demanded there where his work lies; and nowhere else. It is the duty of every man to find his proper sphere. His only appropriate position is therein; and there to keep himself; there to make his activities; there to put forth his energies. It is this finding ones place and keeping it which is integrity, character, honesty, and humility.”

Integrity, character, honesty, humility.

Crummell possessed these qualities in abundance.

They are qualities we too must cultivate in our vocations.

What will we do when our seed falls on rocky places?

Crummell’s life makes us look at this parable with fresh eyes, and realize that even the rocky places need cultivation and care.

Of course, those rocky places are all around us.

The rocky places of a self-absorbed culture.

The rocky places where violence and profit margins are easier than peace and justice.

The rocky places where the Gospel is ignored, the Spirit resisted.

The rocky places where a person, or a church, would rather die than change.

The rocky places where racism abounds, even in nations that claim equality under the law.

You have been in rocky places.

You might be in one now.

You certainly will find yourself in one in the future.

In order to do work in the rocky places, it is good to attend to the teachings of the Letter of James.

To do work in these places takes faith, which in its testing produces endurance.

This testing brings one’s faith to a place of maturity and fullness.

I imagine this was the faith of Alexander Crummell.

He worked in those hard and rocky places, and nonetheless worked at nurturing the faith of others in those places.

This takes me back to the image of that seed falling in the rocky soil.

I want to offer a midrash on this parable.

A midrash is a Jewish way of interpreting Scripture that offers another reading to get at the truth of a story.

Here’s the midrash.

There was seed sown in rocky soil and the seeds grew.

A worker came to the field every day and watered the plants but the sun caused them to wither.

One night while the worker slept, the master of the field came and replaced the rocky soil with good soil.

And the plants grew and bore fruit tenfold, twentyfold, and a hundredfold.

And the worker came to the field and rejoiced.

When you find yourself in those rocky places, remember Alexander Crummell.

Keep your hand to the plough.

Tend to the seeds of the gospel.

Trust in God.

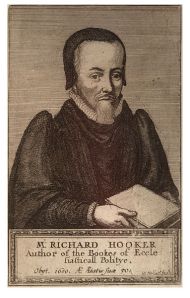

A Four-Legged Stool? Blogging Richard Hooker on Ecclesiastical Polity

In his disputation with Puritans, Richard Hooker assumes that people on both sides of the argument agree on basic theological matters and participate in a broadly reformed consensus shared with Protestant counterparts in continental Europe. So Hooker’s argument with Puritans rests in matters of practice, or what he describes in the title of Book V, chapter 6 as “the outward publique ordering of Church affaires.”

In his disputation with Puritans, Richard Hooker assumes that people on both sides of the argument agree on basic theological matters and participate in a broadly reformed consensus shared with Protestant counterparts in continental Europe. So Hooker’s argument with Puritans rests in matters of practice, or what he describes in the title of Book V, chapter 6 as “the outward publique ordering of Church affaires.”

Hooker sets out four propositions for evaluating arguments over the ordering of the Church. As mentioned in a prior post, he draws these arguments from the Preface and the statement “Of Ceremonies” in the 1552 Book of Common Prayer. These principles are that of reason, ancient practices of the Church, ecclesiastical authority, and equity. It is a commonplace to argue that Hooker introduces a three-fold hermeneutic of Scripture, tradition, and reason into Anglicanism, commonly referred to as a three-legged stool. Yet nowhere does Hooker explicitly lay out this hermeneutic. In light of his proposals here, one could just as easily refer to a four-legged stool for evaluating Anglican ecclesiology and practices. A quick look at these four propositions is fruitful.

Regarding reason, it is important to keep in mind that Hooker does not understand reason in our contemporary sense of something like common sense or rational deliberation or personal insight. Rather, reason for Hooker is aligned with the concept of natural law, that there are universal principles of the universe ordained by God. Humans, made in the image of God, operate according to natural law. Reason is one of the clearest ways that humans operate according to natural law. In this sense, Hooker can speak of reason this way: “In the powers and faculties of our soules God requireth the uttermost which our unfained affection towards him is able to yeeld” (V.6.1). Reason is one way in which humans know how to and are capable of conforming themselves to God. Crucially, religion, especially the act of worship, as expressed in the life of the Christian Church is the vehicle for this conformity. Furthermore, because there is one God and one natural law, so also there ought to be only one form of religion for any given commonwealth so that all can alike perform worship of the one God. This first proposition is designed to militate against the Puritan view that multiple approaches to the worship of God might be possible in any given commonwealth.

Hooker’s second proposition concerns ancient practices of the church. He argues that any practices in the life of the Church must be taken seriously if they have been “allowed as fitt in the judgment of antiquitie and by the longe continewed practise of the whole Church” (V.7.1). Here Hooker resists the Puritan charge that existing practices in the Church of England should be eliminated because they are not found within the New Testament. Affirming the importance of the traditions of the Church, Hooker counters with a general rule of thumb for evaluating practices. “Whereby wee are taught both the cause wherefore wise mens judgments should be credited, and the meane how to use theire judgments to the increase of our own wisdom. That which showeth them to be wise is the gatheringe of principles out of theire owne particular experimentes. And the framinge of our particular experimentes according to the rule of their principles shall make us such as they are” (V.7.2). In other words, wisdom is a collective process. Long standing practices are sustained by a collective discernment of the wisdom of past practices preserved in the contemporary life of the Church. Change in practices then should be undertaken judiciously. “In which consideration there is cause why we should be slow and unwillinge to chaunge without verie urgent necessitie the ancient ordinances rites and long approved customes of our venerable predecessors” (V.7.3).

The third proposition of Hooker’s concerns ecclesiastical authority to make decisions about practice. As he notes, “All thinge cannot be of ancient continewance whoch are expedient and needfull for the orederinge of spirituall affares: but the Church beinge a bodie which dyesth not hath alwaies powers, as occasion requireth, no less to ordeine that which never was, then to ratifie what hath bene before” (V.8.1). In other words, the Church itself can ordain new practices or laws; it can also abolish pre-existing ones. In both cases, Hooker says, the Church “doe well” (V.8.2). But this authority to alter practice does not extend to doctrine. “But that which in doctrine the Church doth now deliver rightlie as a truth, no man will saie that it may hereafter recall and as rightlie avoutch the contrarie. Lawes touching matter of order are changeable, by the power of the Church; articles concerning doctrine not so” (V.8.2.). In other words, Hooker argues that the Church of England properly embraces the universal faith of the Church as represented especially in the core doctrines of the Incarnation and the Trinity (more on the Incarnation later in Book V). But Hooker, arguing against the Roman Catholic and Puritan perspective of that period, also holds that each local Church (here England) can adapt its order and practices as befitting it. In other words, neither the polity of Rome or that of Geneva is fitting for England but that represented in the current structure of the Church of England at his time are most fitting.

The three-legged stool is a popular distillation of Richard Hooker’s theological method. While he himself never uses that concept, I believe a toehold for it as popularized by later writers is embedded in this chapter. As he tries to explain how a Church can appropriately decide how to alter or retain aspects of its order, he writes “Be it in matter of one kinde or of the other, what scripture doth plainelie deliver, to that the first place both of creditt and obedience is due; the next whereunto is whatsoever anie man can necessarelie conclude by force of reason; after these the voice of the Church succeedeth. That which the Church by her ecclesiasticall authoritie also shall probablie think and define to be true and good, must in congruitie of reason overrule all other inferior judgmentes whatsoever” (V.8.2). Here we find embedded the three legs of the fabled stool of Hooker: Scripture, tradition, and reason. Three things stand out to me. First, if this is a locus for Hooker’s stool, it is a decidedly wobbly stool. Scripture is clearly set apart as a primary locus of authority. Second, reason here again means something that is clearly discernible to any person. Reason then is not a private realm of personal interpretation or insight in the modern sense but rather a commonly held consensus. Finally, the function of this method is limited to the areas of order, polity, and practice. Theological doctrines around which the Church has derived consensus, especially Christological and Trinitarian doctrines, are not a subject for this approach.

Hooker’s fourth proposition is that of equity. By this he means all of the grey areas in which church polity, as with any institution, necessarily operates. Here he states, “when the best thinges are not possiblem the best maie be made of those that are” (V.9.1). Implicit in this is the notion that no Church polity or governance is in itself perfect. Rather, allowances must be made on a regular basis for contingent circumstances in matters of order and polity. The specific issue lying behind this was Puritan concerns over ecclesiastical appointments. Hooker here argues that ecclesiastical appointments ought to occur on the basis of equity rather than abiding by hard and fast rules. Day to day affairs often need to be ordered according to the principle of equity as applied to widely diverging circumstances.

Following upon his four principles of reason, ancient practices of the Church, ecclesiastical authority, and equity, Hooker elucidates the principle that the “rule of mens private spirits [are] not safe in these cases to be followed” (V.10). Hooker urges that in matters where “the worde of God leaveth the Church to make choise of hir own ordinances, if against” the four principles he has set forth “it should be free for men to reprove, to disgrace, to reject at theire owne libertie what they see done and practised accordinge to order set downe . . . what other effect could hereupon ensewe, but the utter confusion of his Church under pretense of being taught, led, and gudied by his spirit” (V.10.1). In other words, when deciding upon matters of order and practice for the Church of England, these four principles are the means of discerning a way forward. Crucially, Hooker urges against individual interpretation of these matter or competing approaches followed by one congregation in one place and another approach by a congregation in a different place.

This final point helps us appreciate Hooker’s larger attempt to elucidate his four proposition for ordering the life of the Church of England. Against the his fear of a sectarian Puritan impulse, Hooker emphasizes a collective approach that mitigates against individualized interpretations or application concerning order and practice. This is a stance against an individual or sectarian application of reason or experience or interpretation of tradition. Whether one decides to imagine Hooker proposing a four-legged stool of reason, ancient practices of the Church,ecclesiastical authority, and equity or a traditional interpretation of Scripture, tradition and reason as a sort of three-legged stool, one must remember that Hooker envisions a method that is performed collectively for the life of the entire Church. It concerns order and practice, not settled doctrine. Personal preferences and insights are not the drivers of the decision making process but rather a consultation of a collective repository embedded within the life and structures of the Church itself.

Filed under Ecclesiology, Episcopal Church and Anglicanism, Richard Hooker

Renunciation of Discipline in South Carolina?

In the link above, the news came out today that “The Disciplinary Board for Bishops has advised Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori that the majority of the 18-member panel has determined that Bishop Mark Lawrence of the Diocese of South Carolina has abandoned the Episcopal Church “by an open renunciation of the Discipline of the Church.”

While I am disquieted by the moves that Bishop Mark Lawrence has made regarding canonical changes as part of apparent efforts to ensure that parishes in the Diocese of South Carolina revert to the diocese and not The Episcopal Church in the case of a split, I have difficulty with the finding that these moves in themselves entail “an open renunciation of the Discipline of the Church.”

Bishop Lawrence has participated in the life of the church. Even with the events of General Convention that he and his deputation found difficult, even when most of the deputation left Convention early this summer, there still seems to have been an effort of Bishop Lawrence to keep walking with TEC. I fear that this ruling has ensured another schism in our life.

I suspect in many ways I view the Episcopal Church and its trajectory differently from the leadership of the Diocese of South Carolina yet I desire to remain in relationship with them. The ruling of the Disciplinary Board, while legally correct perhaps seems to me to have been a misstep for the larger goal of preserving the unity of the church.

Filed under Episcopal Church and Anglicanism

Sermon on the Commemoration of Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley

Zephaniah 3:1-5

Psalm 142

1 Corinthians 3:9-14

John 15:20-16:1

All Saints Chapel

Church Divinity School of the Pacific

October 16, 2012

Dr. Daniel Joslyn-Siemiatkoski

“For we are God’s servants, working together; you are God’s field, God’s building.” (1 Cor 3:9)

On October 6, 1555 the former bishops of Worcester and London, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, were executed by burning at the stake in Oxford.

Latimer and Ridley were tireless advocates of the Protestant Reformation as it unfolded in England.

They had worked diligently in advancing it during the reigns of both Henry VIII and Edward VI.

They stood for the great Reformation principles of Scripture, preaching, and worship in the language of the people.

And they died as staunch defenders of Protestantism, defying Queen Mary’s efforts to re-establish Roman Catholicism in England.

In Oxford there stands the Martyr’s Memorial to commemorate Latimer, Ridley, and Thomas Cranmer.

The history of this monument matters.

In the 1850s, this monument was erected by those opposed to the rise of Anglo-Catholicism.

Opponents of the so-called Oxford Movement, like the priest Charles Golightly, envisioned this monument to Protestant bishops martyred at the hands of a disgraced Catholic queen as a rebuke to the followers of John Henry Newman, Edward Pusey, John Keble, and the like.

The inscription on this monument reads in part:

“To the Glory of God, and in grateful commemoration of His servants, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Prelates of the Church of England, who near this spot yielded their bodies to be burned, bearing witness to the sacred truths which they had affirmed and maintained against the errors of the Church of Rome, and rejoicing that to them it was given not only to believe in Christ, but also to suffer for His sake”

But around this monument there stand other structures, symbols of the Catholic revival in the Church of England.

The Martyr’s Memorial is just next to St. Mary Magdalene’s which became an Anglo-Catholic bastion in the 20th century.

Just up the road from the Martyr’s Memorial is Pusey House and its chapel, a historically important center for advancing the Anglo-Catholic movement.

One can look at the ecclesiastical geography of Oxford as a story of the on-going divisions within the Church of England concerning reform, catholicity, authority, and piety.

And we must remember that there were martyrs on all sides of the Protestant-Catholic divide in England and throughout Europe.

While there is something awe-inspiring in the willingness of a martyr to die for the sake of Christ, there is something horrifying when the executioner is another Christian.

Martyrs die out of the conviction that one is a member of a Church that rests upon the true foundation of Jesus Christ.

The death of a Christian at the hands of another undermines confidence in the nature of that very Church.

The execution of Latimer and Ridley under Mary, or Jesuits like Edmund Campion under Elizabeth, or even the divisions between Evangelicals and Catholics in later Anglicanism, show cracks in the edifice of God’s Church.

Paul addressed the problem of fissures threatening to bring down the Church in his first letter to the Corinthians.

Paul reminds us that amidst our awful divisions, we must acknowledge that no one party or faction can claim the Church for themselves.

“Each builder must choose with care how to build on it. For no one can lay any foundation other than the one that has been laid; that foundation is Jesus Christ.” (1 Cor 3:10-11)

There is no doubting the deep faith of Latimer or Ridley or any other Protestant or Catholic martyrs from this era.

But the showdown of competing edifices in Oxford – a Martyr’s Memorial here, an Anglo-Catholic chapel there – in a spirit of striving or rivalry must give us pause.

Paul urges not to let our differences define us but to look to Christ as the only and true foundation.

We must not enshrine our differences.

And we should look to our words and actions.

We should look closely at our assumptions and our certainties about our take on the Church.

Do we speak about other Christians disparagingly?

Have we broken ourselves up in factions?

Do we give off subtle messages of superiority if we set ourselves apart by our piety or our speech about other Christians?

Do we introduce divisions when we should seek unity?

Paul warns the Corinthians, he warns us, he warned Christians in the the sixteenth century, that builders and buildings are tested by fire while in this world.

We do not build Churches for ourselves.

We are all alike laboring in service to God’s plans laid down for the Church.

And that plan is to worship God and to proclaim the Good News of Jesus Christ.

Let us work together as one body, equally serving God, so together we can pass through the fire to be God’s Church together for the sake of the Gospel and for the sake of the world.

On Maps and Mission

So I have been looking at the recently released data from the 2010 US Religion Census. The Episcopal Church has 1.9 million members according to the latest figures. (This is down from the historic high water mark of 3.4 million in the 1960s.) In most US counties where TEC is present (and there are plenty where it is not), the average number of Episcopalians is at or below 1% of that county’s population. Now, as the Crusty Old Dean has reminded us, the Episcopal Church has never been numerically large. But the visual graphics are striking. Here is the map I am talking about:

So, red is the highest population of Episcopalians (mostly around Native American reservations), clocking in at 5% or higher of the population. Then you get a nice smattering of oranges in the traditional East Coast bases of the church. But even there we are only talking about 1% to 4.99% of the population. Then the yellows and greens (like where I live in California) show where less than 1% of the population is part of the Episcopal Church. Then take a minute and look at all the grey area. County upon county where the Episcopal Church is not present. Sure, you can point to the middle of the country and say, well, no one lives there. But that would be a lie. And you see many counties with solid population centers. The Episcopal Church just is not there.

Some would look at this map and see a map of the decline and near-collapse of the Episcopal Church.

Not me.

I look at that map and see a great option for the mission of proclaiming the Anglican way of living out the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

I don’t see decline. I see new opportunities for ministry and mission.

Do you?

Filed under Episcopal Church and Anglicanism, Mission, Technology

Projects | Don’t Shoot the Prophet

Projects | Don’t Shoot the Prophet.

If you want to read some of the talks from the meeting in Krakow about planting an Episcopal Church congregation in Poland, click on the link above. Polish version is also available at that site.

Filed under Cracow, Episcopal Church and Anglicanism, TEC in Europe

Bringing the Episcopal Church to Poland

Bringing the Episcopal Church to Poland.

Episcopal News Service published my thought on what the Episcopal Church can learn from the outcomes of the workshop in Krakow that I helped lead this past weekend. Click the link above to read it.

Filed under Cracow, Episcopal Church and Anglicanism, TEC in Europe

Why an Episcopal Church in Poland?

Something new happened in Krakow this Saturday. People gathered in an upper room of St. Martin’s Lutheran Church to spend a day together learning about the Episcopal Church and discerning whether it is God’s will that an Episcopal community be established in Poland.

People gathered from all over Poland representing the range of Polish Christianity. There were Lutherans, Roman Catholics, Old Catholics, and Mariavites. People came from Krakow, Warsaw, Czestochowa, Poznan, and beyond. The participants were male and female, gay and straight, with the vast majority under 40 if not 35. Bishop Pierre Whalon of the Convocation of Episcopal Churches in Europe, his wife Melinda, and myself acted as representatives and ambassadors for the Anglican expression of Christianity found in the Episcopal Church.

Those gathered did what Christians have always done. They prayed. They learned from one another. They shared a meal. They talked together, discerning what God might be doing among them. And they worshiped together. In fact, history was made as the celebration of the feast of John Donne, presided by Bishop Whalon, was the first celebration of the Episcopal liturgy in the history of Krakow. And unlike the great barriers that exist between Protestant and Roman Catholic bodies in Poland, all were welcomed to receive communion and all who desired this did.

As we discerned together, it soon became clear that those who had come to this meeting keenly felt the need for an Anglican way in Poland. As one person noted, there are many Christians in Poland who cannot finds themselves in the Roman Catholic Church, the Polish Old Catholic Church, or the various Lutheran, Methodist and Reformed churches that make up the Polish Ecumenical Council. There is no church in Poland that is rooted in the Catholic traditions of the ancient church, ordered according to the apostolic succession and retaining the primacy of scripture while also admitting all people to ordained ministry, including women and members of the LGBT community.

The Episcopal Church is especially attractive because it is located in a wider communion and tradition. It is not one of the many sectarian movements that have sprouted up among disaffected Christians in Poland over the past twenty years. The Episcopal Church has a clear set of doctrinal teachings that are minimally defined so that people may engage with the teachings of the church in a reflective way.

The baptismal ecclesiology of the Episcopal Church offers a means of equipping laity for ministry in Poland. This is a radical departure from Polish Christianity which has traditionally fostered an attitude where the clergy dispense the gifts of the church to the laity without including them deeply in the ministry of the church. Given that the mission of the Convocation of Episcopal Churches in Europe is to foster local expressions of the Episcopal Church, there is support for an ongoing project to translate the BCP and other resources into Polish. Those who celebrated the Eucharist with us in Polish found it familiar and comfortable.

In other words, the Episcopal Church has a tremendous opportunity to offer a way of being Christian in Poland to those who are looking for a church that adheres to ancient traditions but flings wide its doors to include all people – male and female, gay and straight, lay and ordained – into its ministry of carrying out God’s mission in the world.

As the workshop concluded people expressed gratitude, joy, and a willingness to journey onwards. Some important things were learned. One was that it appears Krakow is not the best location for starting a community. More interest appears to exist in the west and north of Poland. As a result, one of the next steps is to organize a retreat in Anglican spirituality for interested people from this workshop and elsewhere to be held at the end of June in Poznan, a large university city in the west.

I am not certain what I thought would happen this weekend. On the one hand, I was very hopeful and optimistic. On the other hand, I knew a church could not blossom in a day. Church planting is just that, planting. A lot needs to happen on the way from a seed to a tree. This weekend the Spirit’s presence allowed us to break open the soil, scatter some seeds, and pour some water. But more working of the soil, more scattering of seeds, more nourishing with water is needed. God will grow this tree if it is meant to take root. Pray for good soil, fertile seeds, and plentiful water as this work unfolds.

The Episcopal Church in Cracow?

Tomorrow I am getting on an airplane bound for Cracow. Although I have always wanted to visit my ancestral homeland, I never imagined I would be going to Poland as a church planter. But that looks like what is happening. You see, I have received a generous grant from the Evangelical Education Society to help lead a workshop on starting an Episcopal Church congregation in Cracow. My partners in this are Jarek Kubacki and Lukasz Liniewicz who run a bilingual Polish/English blog Don’t Shoot the Prophet.

When Jarek and Lukasz began the blog in 2009, their purpose was to portray the Episcopal Church in a positive light to Poles who only ever heard about the church in the context of controversy and schism. But the interest generated by the blog has developed so that they began to receive inquiries about how an Episcopal Church community could start in Poland. And with that has grown the workshop this weekend. At it I will speak on Anglicanism and the Episcopal Church as expressions of reformed catholicity expressed locally. Jarek and Lukasz will lay out how they envision an indigenous Polish expression of the Anglicanism rooted in the life of the Episcopal Church. And Bishop Pierre Whalon will speak on how the Convocation of Episcopal Churches in Europe understands itself and can assist in developing a church in Cracow.

In the next days I will write more about why the Episcopal Church might be well suited for Poland. I will also provide updates about the workshop itself.

Until then, please pray that the events on Saturday unfold in ways that are Spirit-led and infused with a desire to continue Christ’s reconciling mission in the world.

Filed under Cracow, Episcopal Church and Anglicanism